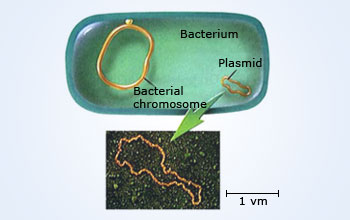

Bacterial chromosome

In contrast to the linear chromosomes found in eukaryotic cells, the strains of bacteria initially studied were found to have single, covalently closed, circular chromosomes. Bacterial plasmids were circular. In fact, the experiments were so beautiful and the evidence was so convincing that the idea that bacterial chromosomes are circular and eukaryotic chromosomes are linear was quickly accepted as a definitive distinction between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells.

Bacterial chromosome

In contrast to the linear chromosomes found in eukaryotic cells, the strains of bacteria initially studied were found to have single, covalently closed, circular chromosomes. Bacterial plasmids were circular. In fact, the experiments were so beautiful and the evidence was so convincing that the idea that bacterial chromosomes are circular and eukaryotic chromosomes are linear was quickly accepted as a definitive distinction between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells.

While the chromosomes of prokaryotes are relatively gene–dense, those of eukaryotes often contain so–called "junk DNA", or regions of DNA that serve no obvious function. Simple single–celled eukaryotes have relatively small amounts of such DNA, while the genomes of complex multicellular organisms, including humans, contain an absolute majority of DNA without an identified function.

However it now appears that, although protein–coding DNA makes up barely 2% of the human genome, about 80% of the bases in the genome may be being expressed, so the term "junk DNA" may be a misnomer.

Eukaryotes (cells with nuclei such as plants, yeast, and animals) possess multiple large linear chromosomes contained in the cell’s nucleus. Each chromosome has one centromere, with one or two arms projecting from the centromere, although under most circumstances these arms are not visible as such.

In addition, most eukaryotes have a small circular mitochondrial genome, and some eukaryotes may have additional small circular or linear cytoplasmic chromosomes. In the nuclear chromosomes of eukaryotes, the uncondensed DNA exists in a semi–ordered structure, where it is wrapped around histones (structural proteins), forming a composite material called chromatin.